Page

Information

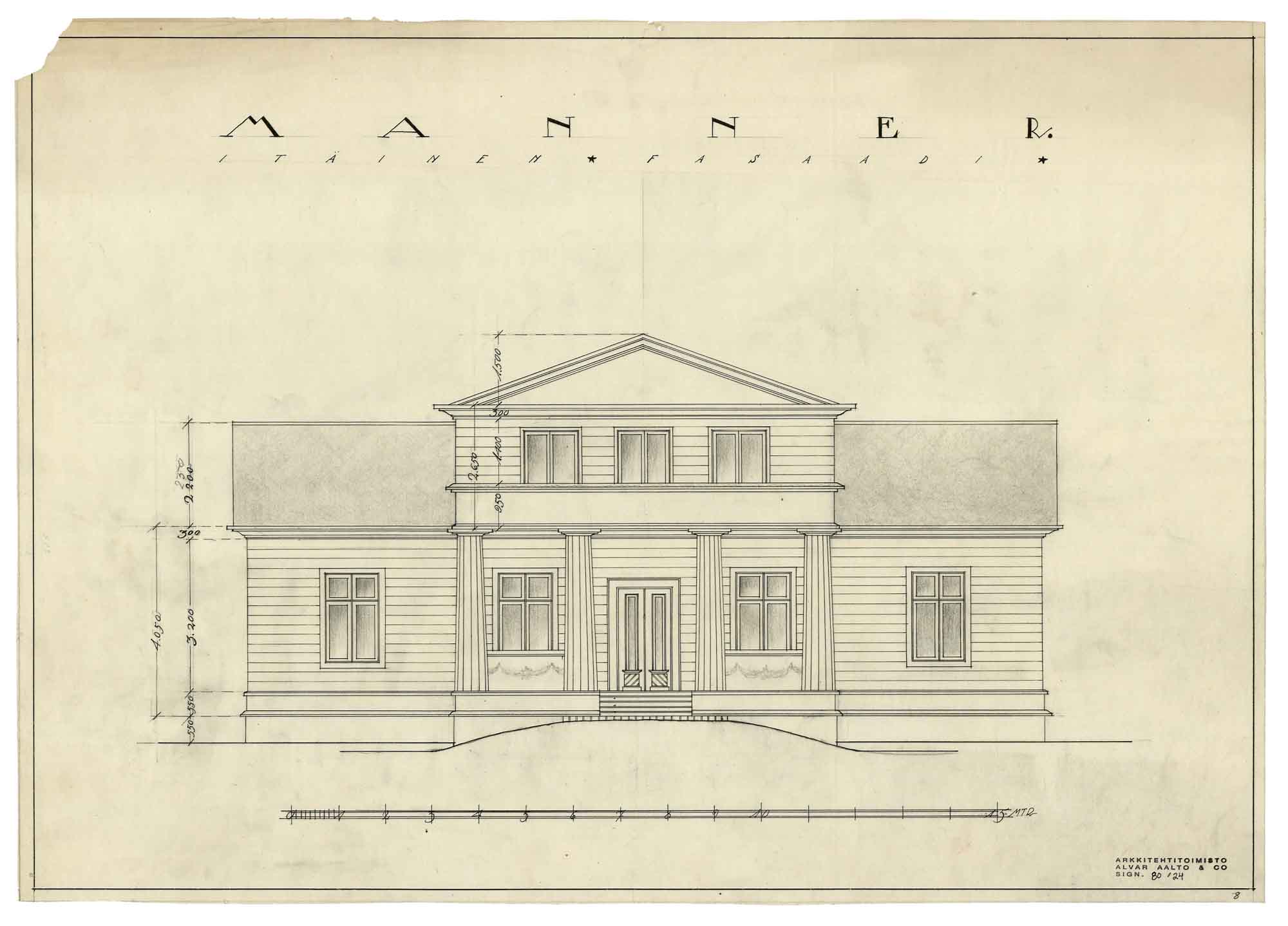

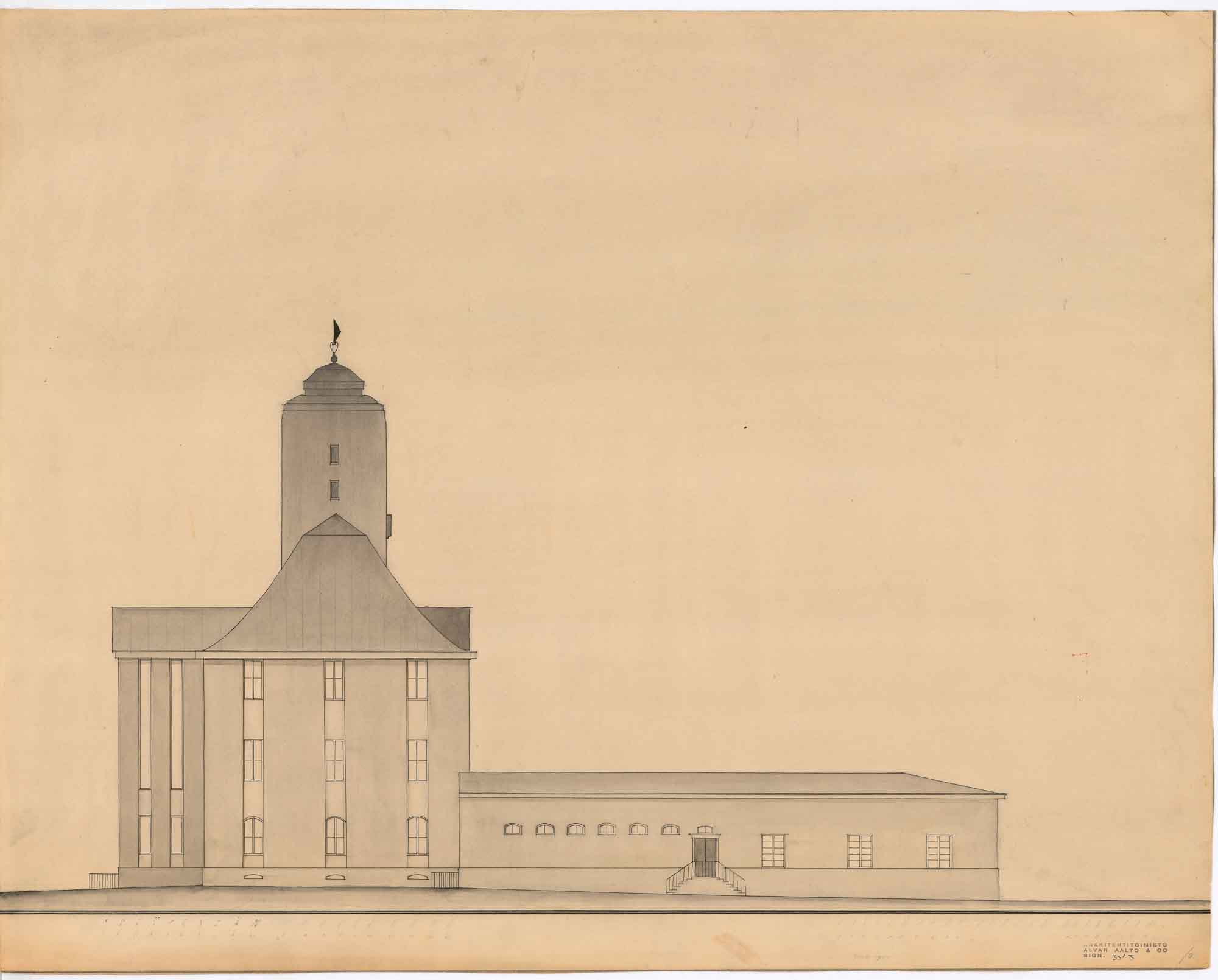

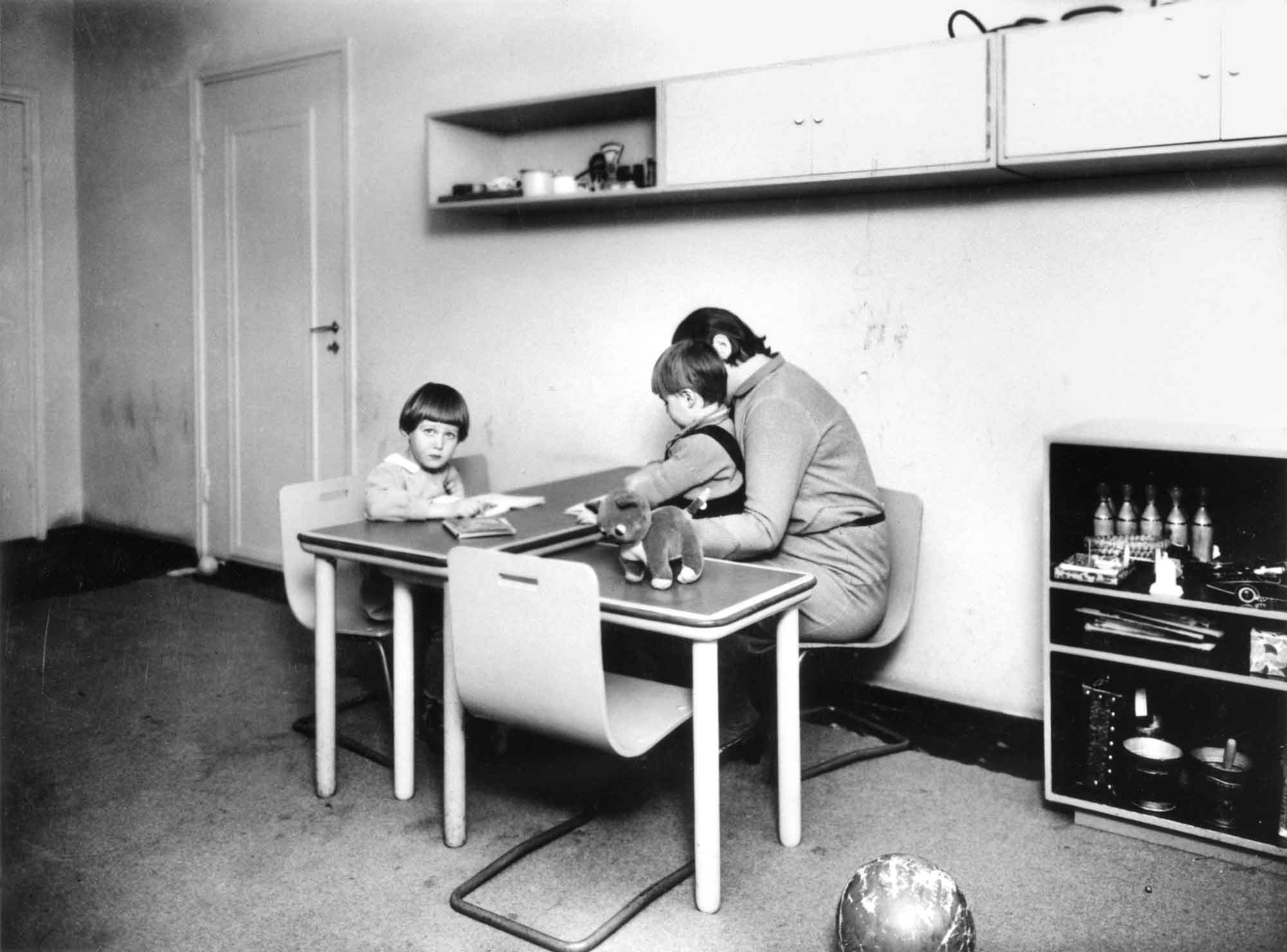

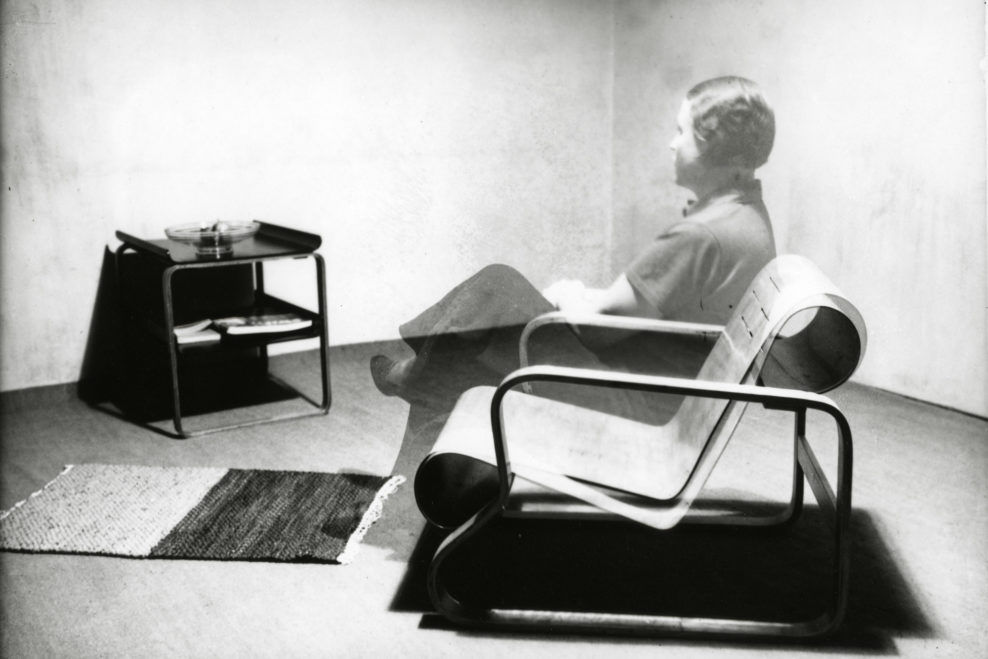

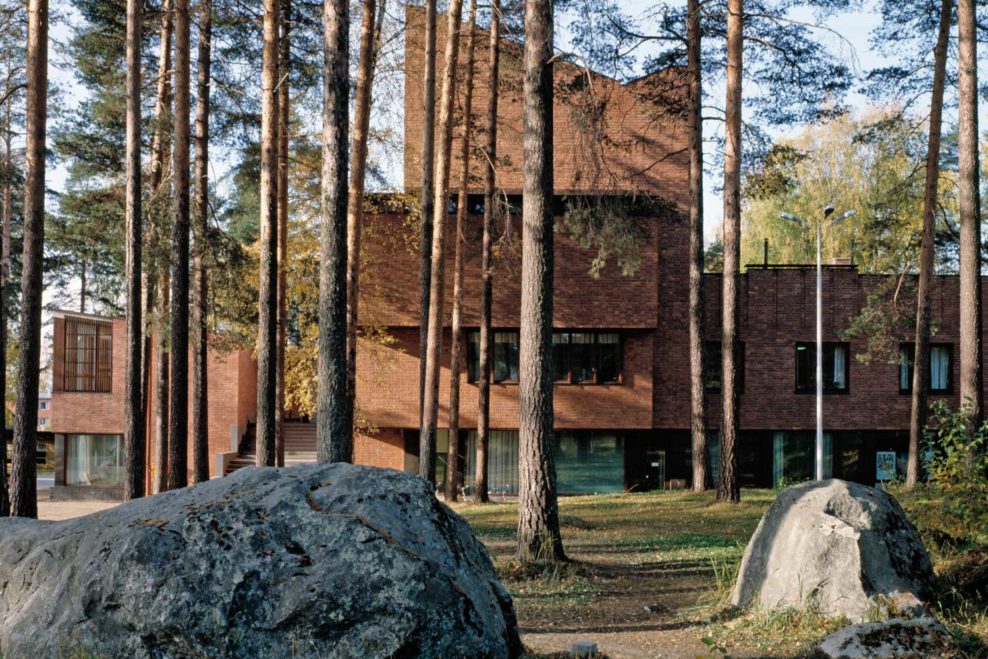

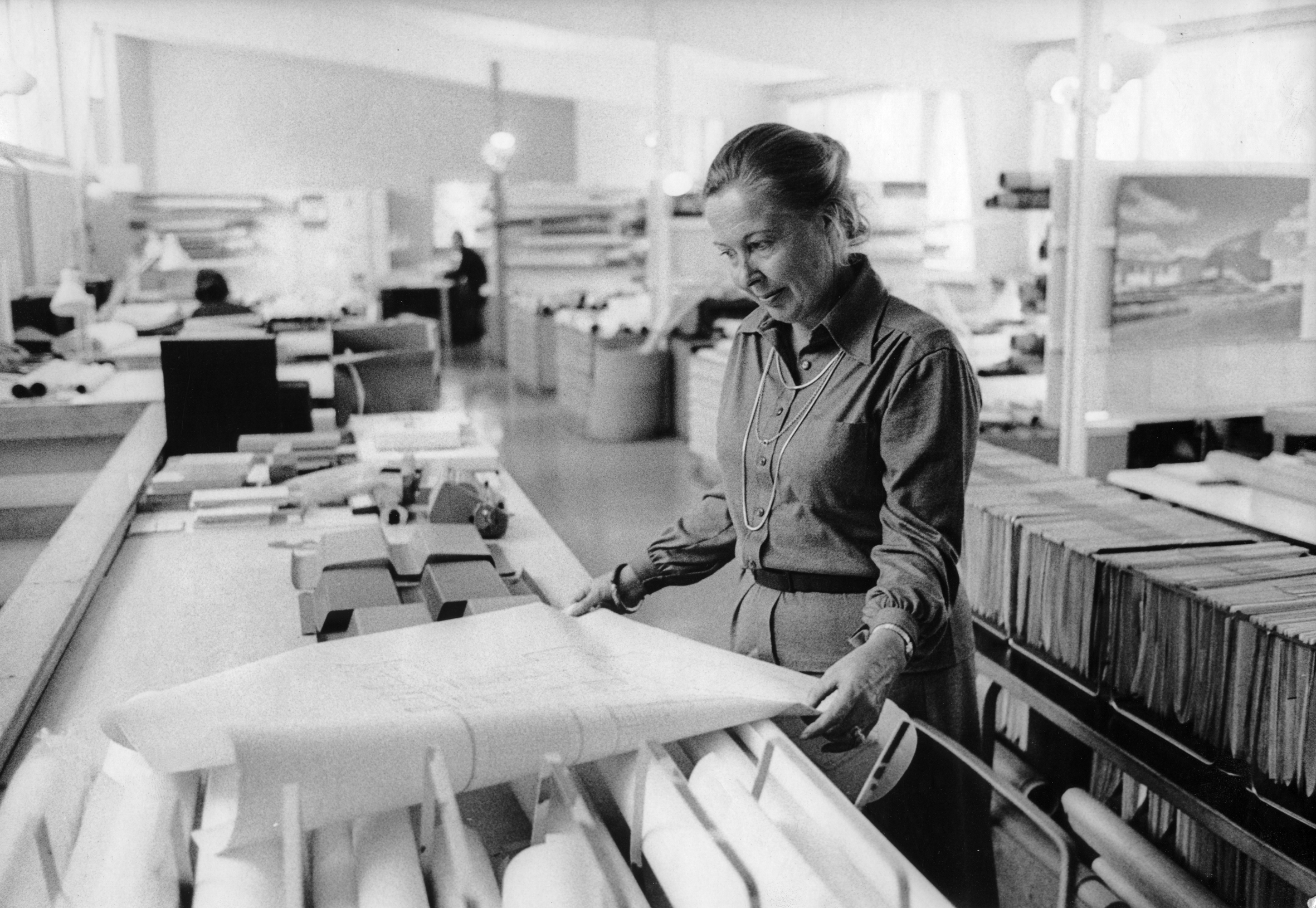

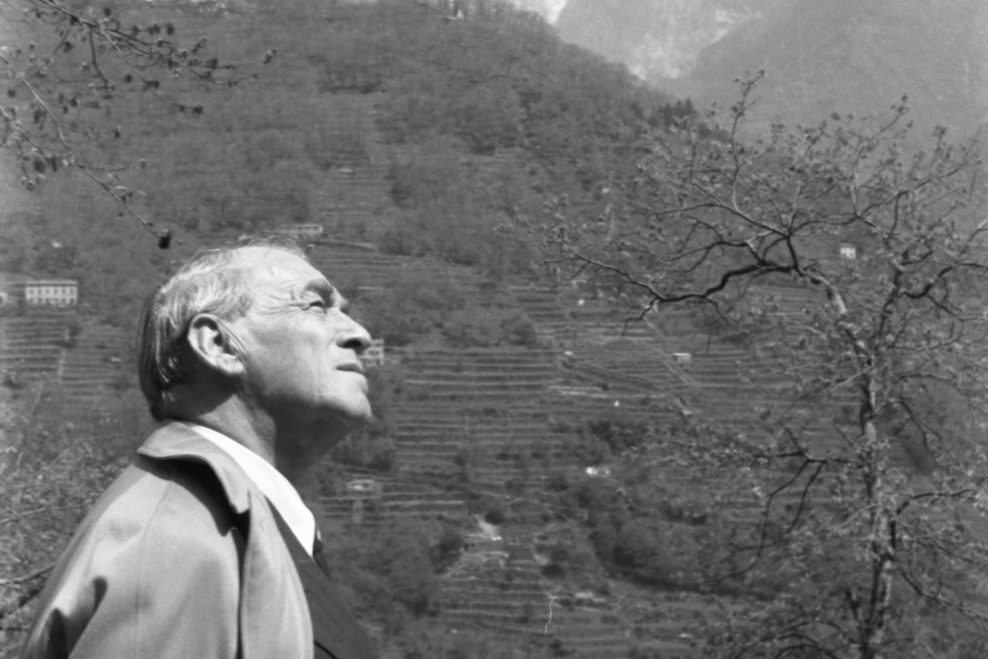

The Alvar Aalto Foundation maintains the material and intellectual legacy of the world-famous architect and designer Alvar Aalto, and acts to make his work and thinking more widely known.

Read more