Seinäjoki Civic Centre

Seinäjoki cultural and administrative centre is based on two architectural competitions. In 1951, Alvar Aalto won the church competition organized by the Parish of Seinäjoki with his proposal Lakeuksien risti (the Cross of the Plains). Seven years later (1958), he also won the competition for Seinäjoki Town Hall organized by the township of Seinäjoki with his proposal Kaupungintalo (Town hall). He was thus given the opportunity to design a complete urban centre.

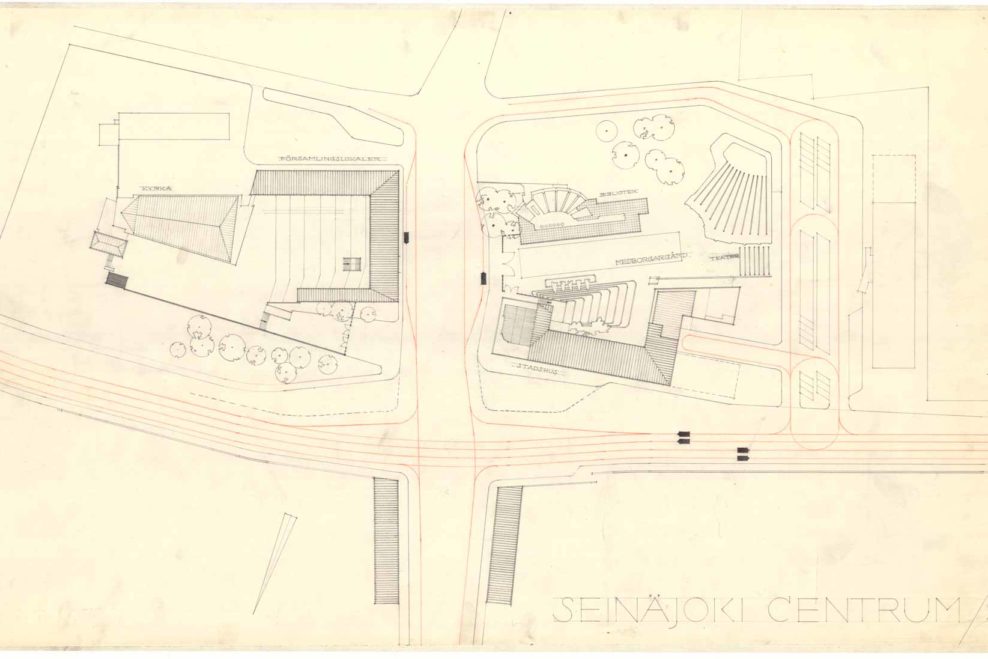

Originally, the church buildings formed an independent complex, as was not decided to locate the administrative and cultural buildings in close proximity to the church until five years later. Although it was possible to take the church buildings into account in the townhall competition, the church buildings and the administrative and cultural buildings were not finally welded together as a city centre until the 1960s after a long series of design stages.

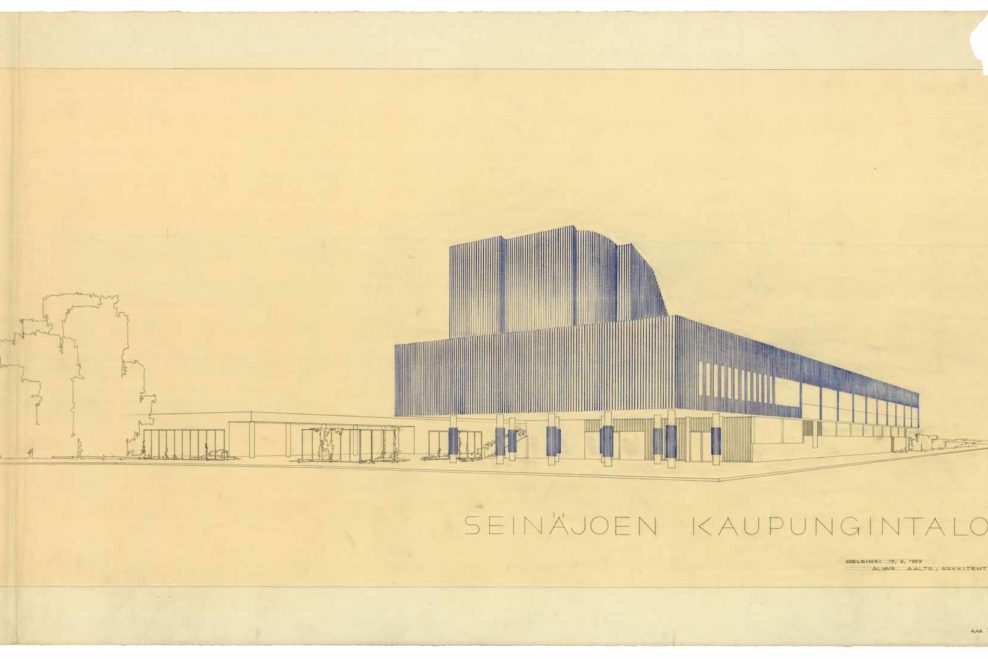

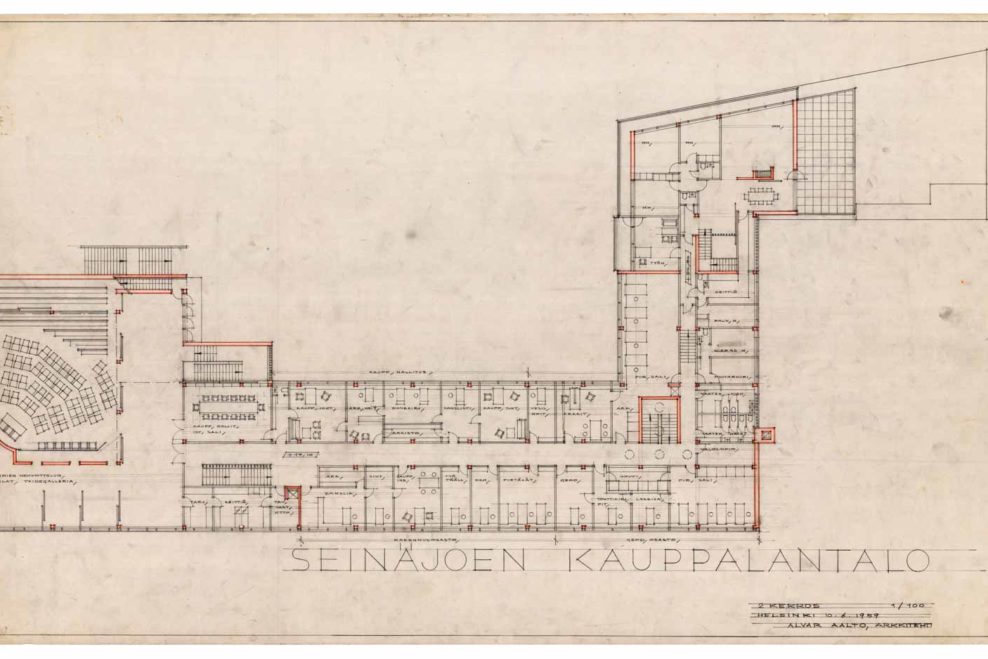

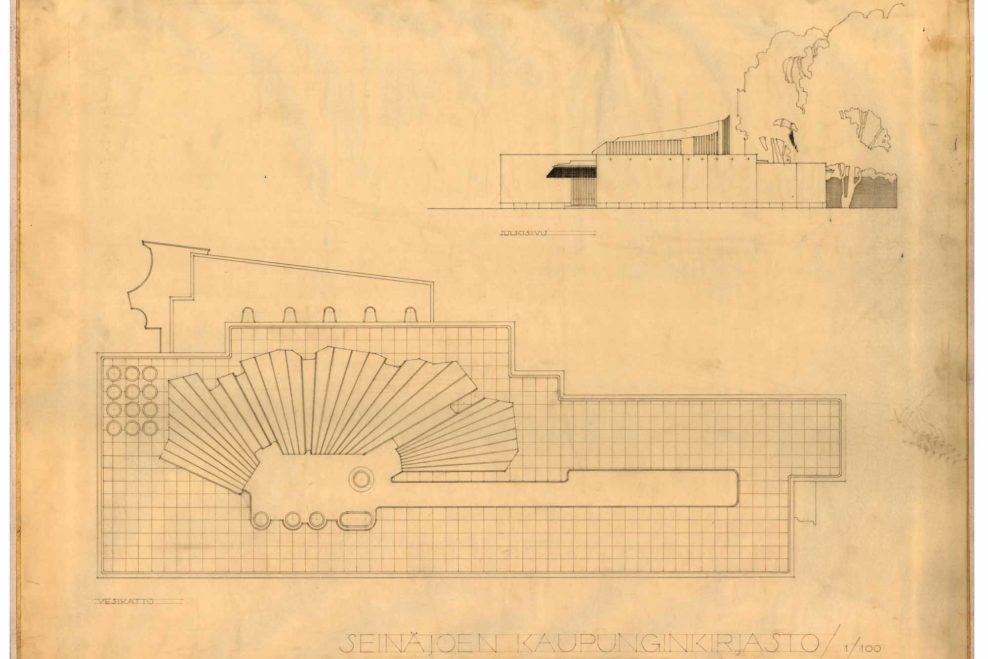

The first of the buildings to be completed was the Church of the Cross on the Plains in 1960, followed by the town hall (1962), the library (1965), the parish center (1966) and the government office building built by the state in 1968. After Alvar Aalto’s death, design of the Seinäjoki centre was continued by his second wife, the architect Elissa Aalto. The Theatre was completed in 1987 and the paving of the square was finished the following year (1988). Because of its varied range of buildings and the fact that it was constructed in full, Seinäjoki cultural and administrative centre is the most representative example of Alvar Aalto’s city centres. There were many of these, but most of them remained on the drawing board.

The Seinäjoki centre consists of a group of public buildings set slightly apart from the rest of the urban structure. However, the most important buildings are delineated and bounded by external spaces, by picturesque courtyards or squares.

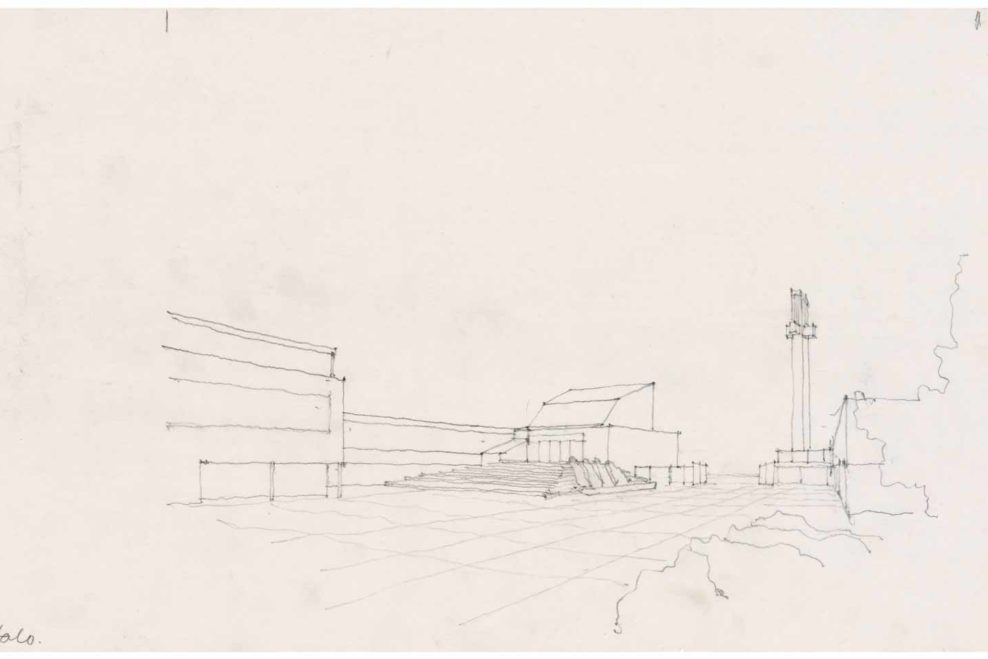

The churchyard, which borders the church and the parish centre, forms a spatial sequence that is reminiscent of early Christian basilicas with their atriums. The churchyard, which is banked up to form an auditorium, is designed with the religious summer festival that are held in Ostrobothnia in mind. In the church competition, Aalto even suggested that the end wall of the church could be made to open so that the altar would have been visible from the courtyard. On the north side of the church there is a forecourt which is terminated to the east by the baptistery and a campanile of bell-tower shaped like a cross, which gives the church its name. With the town hall competition, the forecourt was terminated to the west by the town hall itself, with the council chamber up not unlike the tower of a medieval guildhall.

The town hall, library and theatre also border on a central civic square intended as “a meeting place for the citizens of Seinäjoki and probably as a venue congresses, summer conventions and so on, “as Alvar Aalto pointed out in the report which accompanied his town-hall competition entry. To the east, the paving of the square continues across the street to tie in the administrative and cultural buildings with the church buildings. To the west, the vista from the square which dominates the theatre and the town hall is terminated by the government office building, which was transferred from central government to local government use and ownership in 2003. The predominant façade material in the Seinäjoki centre is white rendering, which is complemented by the black granite of the baptistery, the dark-blue, rod-shaped ceramic tiles of the town hall, the white rod-shaped ceramic tiles to the theatre and the green patina of the copper roofs.

As Alvar Aalto declaimed at the inauguration of the town hall, “Seinäjoki is not content with just one or two public buildings, it has planned a group of public buildings that will bring people together and form a complete spiritual centre for the city.” After the Second World War, it was concerned that urban functions were no longer restricted to living, working, leisure and traffic by the town planning doctrines of 1930s Modernism, but that community interaction was also needed. For this, meeting places had to be built in city centres for local inhabitants as venues for communal festivities, just like the agoras of ancient times and the piazzas of the Middle Ages. This is precisely what Alvar Aalto was intent on achieving at Seinäjoki.

Text: Jaakko Penttilä