Exhibition

The Florence of the North exhibition at the Alvar Aalto Museum opens a window on Aalto’s architecture in Jyväskylä

25.9.2017

Read more

18. 7.

Friday

19. 7.

Saturday

21. 7.

Monday

22. 7.

Tuesday

23. 7.

Wednesday

24. 7.

Thursday

25. 7.

Friday

26. 7.

Saturday

28. 7.

Monday

29. 7.

Tuesday

30. 7.

Wednesday

31. 7.

Thursday

1. 8.

Friday

2. 8.

Saturday

4. 8.

Monday

5. 8.

Tuesday

6. 8.

Wednesday

7. 8.

Thursday

8. 8.

Friday

9. 8.

Saturday

11. 8.

Monday

12. 8.

Tuesday

13. 8.

Wednesday

14. 8.

Thursday

15. 8.

Friday

16. 8.

Saturday

18. 8.

Monday

19. 8.

Tuesday

20. 8.

Wednesday

21. 8.

Thursday

22. 8.

Friday

23. 8.

Saturday

25. 8.

Monday

26. 8.

Tuesday

27. 8.

Wednesday

28. 8.

Thursday

29. 8.

Friday

30. 8.

Saturday

1. 9.

Monday

2. 9.

Tuesday

3. 9.

Wednesday

4. 9.

Thursday

5. 9.

Friday

6. 9.

Saturday

8. 9.

Monday

9. 9.

Tuesday

10. 9.

Wednesday

11. 9.

Thursday

12. 9.

Friday

13. 9.

Saturday

26. 9.

Friday

27. 9.

Saturday

29. 9.

Monday

30. 9.

Tuesday

1. 10.

Wednesday

2. 10.

Thursday

3. 10.

Friday

4. 10.

Saturday

6. 10.

Monday

7. 10.

Tuesday

8. 10.

Wednesday

9. 10.

Thursday

10. 10.

Friday

11. 10.

Saturday

13. 10.

Monday

14. 10.

Tuesday

15. 10.

Wednesday

16. 10.

Thursday

17. 10.

Friday

18. 10.

Saturday

20. 10.

Monday

21. 10.

Tuesday

22. 10.

Wednesday

23. 10.

Thursday

24. 10.

Friday

25. 10.

Saturday

27. 10.

Monday

28. 10.

Tuesday

29. 10.

Wednesday

30. 10.

Thursday

31. 10.

Friday

1. 11.

Saturday

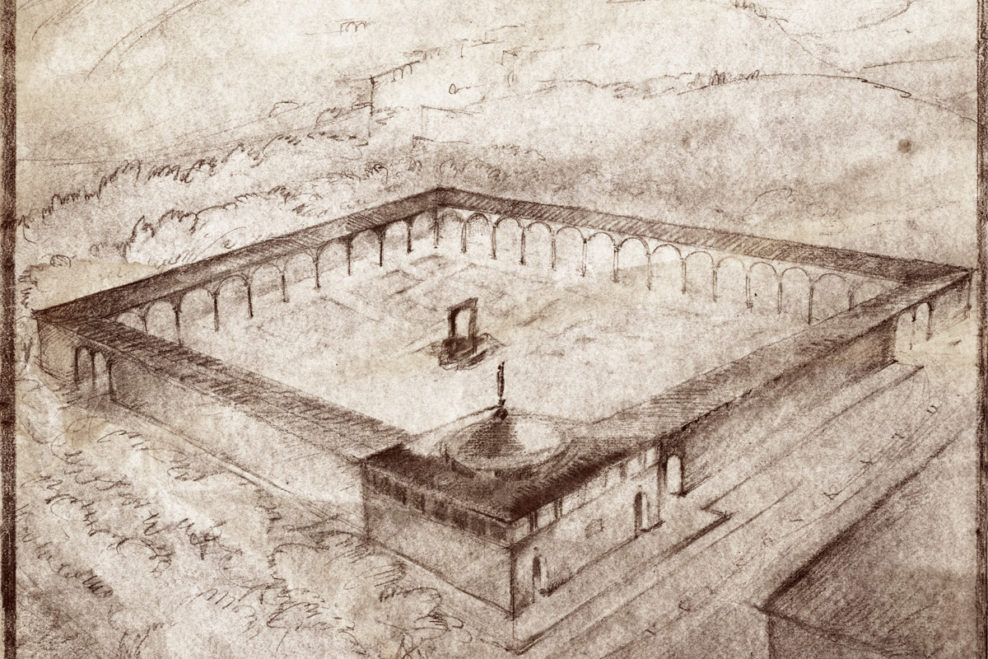

“Central Finland frequently reminds one of Tuscany, the homeland of towns built on hills, which should provide an indication of how classically beautiful our province could be if built up properly.” Alvar Aalto 1925

This exhibition opens a window on some of Alvar Aalto’s unrealised visions and on some of his designs for Jyväskylä, which became reality. Aalto took the first steps of his career as an architect in the city for which he designed dozens of buildings and other projects between the 1920s and the 1970s. In the mind of the architect, the lush, rolling landscape of Central Finland could be compared with the hills of Tuscany. Alvar Aalto’s interest in Antique culture, especially that of Italy, comes to the fore in some of his earliest designs. Jyväskylä has often been called ‘The Athens of the North’, but Aalto thought that ‘The Florence of the North’ was a better description of the city.

To Aalto, Jyväskylä and Central Finland were home, the calf country that was intertwined with his personal history. The schoolboy years of his childhood and youth, the early stages of his career, the establishment of a home and family with the architect Aino Marsio in the 1920s all helped to create a close relationship with the city. Although the path he trod soon led him away to live in the capital and pursue his career there, his work drew him back to Central Finland over and over again. The summer villa he shared with his second wife Elissa, the Muuratsalo Experimental House, on an island in Lake Päijänne strengthened the link with Central Finland from the 1940s and 1950s onwards.

Aalto had an important role as someone who helped to develop the Jyväskylä townscape – indeed the city has a unique and comprehensive display of his architecture from every decade of his career. The range of the designs extends from the smallest, simplest buildings, and alterations to existing ones, to much larger entities such as the master plan for the University of Jyväskylä campus with its numerous buildings constructed between the 1950s and the 1970s, and the Jyväskylä local government area, built in a central part of the City.

Some of the designs which took flight from the architect’s drawing board were never realised. The fate of others was demolition or destruction for some other reason. This exhibition of ‘lost Jyväskylä and lesser-known Aalto’ which is now opening to the public, is a collection of architectural drawings, photographs and objects from the collections of the Alvar Aalto Museum and the deepest recesses of its archives. This exhibition brings together an unprecedented number of Alvar Aalto’s designs for the City of Jyväskylä. In the light of current information, there are 80 of these, some built and some which never left the drawing board.

Timo Riekko, Curator of the Drawings Archives at the Alvar Aalto Museum, tells us that new information is still being found about Aalto’s designs, which supplements the overall picture of the architect’s work. For example, it has just been confirmed that, in the 1920s, Aalto made sketches of a three-storey block of luxury flats in the vicinity of Seminaarinkatu. With its central heating system the building would have been well ahead of its time. It has also been confirmed that the banked-up causeway and bridges shown on the Säynätsalo master plan, linking the island to the mainland, is in accordance with Alvar Aalto’s design, implemented between 1945 and 1947.

There is interest, too, in the fact that this exhibition of local architectural history is firmly linked with the present day. “Aalto’s articles written for the local paper in the 1920s about the market and public saunas still seem to be topical,” says Timo Riekko. Aalto pondered whether Jyväskylä market could be enlivened by the right town planning decisions and the question is still under discussion today when relocation of the market-place to a more central position has aroused lively debate. “Aalto’s suggestion of a public sauna on top of the Harju ridge was not implemented when it was proposed, but today there is a good deal of discussion about whether one should be built somewhere in the rejuvenated harbour milieu of Jyväsjärvi,” points out Riekko.

The Florence of the North – Alvar Aalto’s architecture in Jyväskylä

29.9.2017 – 4.3.2018 Alvar Aalto Museum Gallery

Alvar Aallon katu 7, Jyväskylä, Finland

open Tues–Sun at 11–18

For further information and interviews, please contact:

Mirkka Vidgrén, Communications

mirkka.vidgen@alvaraalto.fi

Tel. +358 40 168 5142